73's and Enjoy, de KB9JJA

FROM

THE "RADIO" HANDBOOK

9th Edition

By Editors and Engineers

1942

The Code

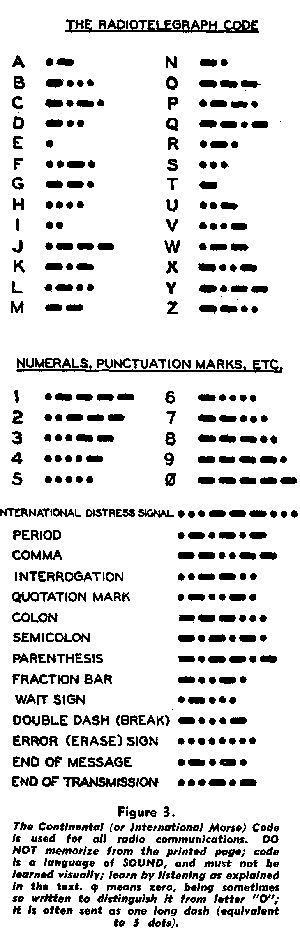

The applicant for an amateur license must be able to send and receive the Continental Code (sometimes called the International

Morse Code) at a speed of 13 words per minute, with an average of five characters to the word. Thus 65 characters must be copied consecutively without error in one minute. Similarly 65 consecutive characters must be sent without error in the same time. Code tests usually last about five minutes; if 65 consecutive characters at the required rate are copied correctly anywhere during the five minute period, the applicant is usually considered to have passed the test successfully. A code speed of 16 words per minute is required for the lowest class of commercial radio operator's license. Higher classes require greater speeds.

If the code test is failed, the applicant must wait at least two months before he may again appear for another test. Approximately 30% of amateur applicants fail to pass the test. It should be expected that nervousness and excitement will at least to some degree temporarily lower the applicant's code ability. The best prevention against this is to master the code at a little greater than the required speed under ordinary conditions. Then if you slow down a little due to nervousness during a -test the result will not prove "fatal."

Memorizing the Code

There is no shortcut to code proficiency. To memorize the alphabet entails but a few evenings of diligent application, but considerable time is required to build up speed. The exact time required depends upon the individual's ability and the regularity of practice.

While the speed of learning will naturally vary greatly with different individuals, about 70 hours of practice (no practice period to be over 30 minutes) will usually suffice to bring a speed of about 13 w.p.m.; 16 w.p.m. requires about 120 hours; 20 w.p.m., 175 hours.

Since code reading requires that individual letters be recognized instantly, any memorizing scheme which depends upon orderly sequence, such as learning all "dah" letters and all "dit" letters in separate groups, is to be discouraged. Before beginning with a code practice set it is necessary to memorize the whole alphabet perfectly. A good plan is to study only two or three letters a day and to drill with those letters until they become part of your consciousness. Mentally translate each day's letters into their sound equivalent wherever they are seen, on signs, in papers, indoors and outdoors. Tackle two additional letters in the code chart each day, at the same time reviewing the characters already learned.

Avoid memorizing by routine. Be able to sound out any letter immediately without so much as hesitating to think about the letters proceeding or following the one in question. Know C, for example, apart from the sequence ABC. Skip about among all the characters learned, and before very long sufficient letters will have been acquired to enable you to spell out simple words to yourself in "dit dahs." This is interesting exercise, and for that reason it is good to memorize all the vowels first and the most common consonants next. Actual code practice should start only when the entire alphabet, the numerals, and period, comma, and interrogation point have been memorized so thoroughly that any one can be sounded without the slightest hesitation. Do not bother with other punctuation or miscellaneous signals until later.

Sound not Sight

Each letter and figure must be memorized by its sound rather than its appearance. Code is a system of sound communication, the same as is the spoken word. The letter A, for example, is one short and one long sound in combination sounding like dit dah, and it must be remembered as such, and not as "dot dash."

As you listen to the sound of a letter transmitted slowly by an experienced operator, you will notice how closely the dots resemble the sound dit and the dashes dah.

You must learn the individual sounds of each code signal so that you associate these instantly with the various specific characters for which they stand. If you attempt to learn by visualizing the dots and dashes, you will never be able to translate them into the characters for which they stand with any degree of speed, so avoid any visualization right from the start.

Practice

Time, patience, and regularity are required to learn the code right. Do not expect to accomplish it within a few days.

Don't practice too long at one stretch; it does more harm than good. Thirty minutes at a time should be the limit.

Lack of regularity in practice is the most common cause of lack of progress. Irregular practice is very little better than no practice at all. Write down what you have heard; then forget it; do not look back. If your mind dwells even for an instant on a signal about which you have doubt, you will miss the next few characters while your attention is diverted.

Take it easy, do not become confused or nervous. Try to ignore the presence of other persons. If you find that they make you nervous, it is a good idea to ask some friends to stand near you and talk to each other while you are practicing. After a few sessions you will become used to external sounds and they will bother you no more.

Each person can learn only so fast; do not try to exceed your natural rate or you will become overanxious and actually slow down your progress.

While various automatic code machines, phonograph records, etc., will give you practice, by far the best practice is to obtain a study companion who is also interested in learning the code. When you have both memorized the alphabet you can start sending to each other. Practice with a key and oscillator or key and buzzer generally proves superior to all automatic equipment. Two such sets operated between two rooms are fine -- or between your house and his will be just that much better. Avoid talking to your partner while practicing. If you must ask him a question do it in code. It makes more interesting practice than confining yourself to random practice.

When two co-learners have memorized the code and are ready to start sending to each other for practice, it is a good idea to enlist the aid of an experienced operator for the first practice session or two so that they will get an idea of how properly formed characters sound. When you are practicing with another beginner don't gloat if you seem to be learning to receive faster than he. It may be that his sending is better than yours. Remember that the quality of sending affects the maximum copying speed of a beginner to a very large degree. If tl;e sending is bad enough, the newcomer won't be able to read it at all and even an old-timer may have trouble getting the general drift of what you are trying to say.

During the first practice period the speed should be such that substantially solid copy can be made without strain. Never mind if this is only two or three words per minute. In the next period the speed should be increased slightly to a point where nearly all of the characters can be caught only through conscious effort. When the student becomes proficient at this new speed, another slight increase may be made, progressing in this manner until a speed of about 16 words per minute is attained if the object is to pass the amateur 13-word per minute code test. The margin of 3 w.p.m. is recommended to overcome a possible excitement factor at examination time. Then when you take the test you don't have to worry about the "jitters" or an "off day."

Speed should not be increased to a new level until the student finally makes solid copy with ease for at least a five-minute period at the old level. How frequently increases of speed can be made depends upon individual ability and the amount of practice. Each increase is apt to prove disconcerting, but remember "you are never learning when you are comfortable."

After the war's end it is probable that a number of amateurs will again send code practice on the air on schedule once or twice each week; excellent practice can be obtained after you have bought or constructed your receiver by taking advantage of these sessions. A stamped, self-addressed envelope accompanying in inquiry to the American Radio Relay League, West Hartford, Connecticut will bring a list of the stations transmitting code practice in your vicinity. If you live in a medium or large city, the chances are that there is an amateur radio club in your vicinity which will resume free code practice classes when amateur radio transmission is again permitted.

Practice Material

At the start use plain English, sending from a book, newspaper, or anything handy. Also practice disconnected words from the list on page 11, which is said to contain about half the words commonly spoken in English.

More detailed instructions on code learning practice may be obtained from several text books which are written to cover this subject exclusively.*

- * The Radio Code Manual, 174 pages, containing general instructions, 20 code lessons with practice material, how to build code practice equipment, and how to operate a code class, may me obtained from out book department for $2.00 plus six cents postage (add tax in California).

MYOFFSAIDDOWNAWAYANPAYONLYOTHERGIVEOFENDWOULDLIKEHIGHDOANDTHENUNDERINTERESTITKEYLONGHEARHIMSELFUPNOTMANYDONTFACTAMPERBECAUSEALSOWITHOUTNOHISYOURDOESANOTHERHEOWNKNOWYOURSPURPOSEORPUTOVERHALFPOWERINHERWHENEACHDONETOAREFROMWHERENAMEASOWESOMETODAYSMALLMEALLWERELASTBELIEVEGODIETHEREONCESTANDWENEWWELLSAYSTHINKBEauyTHEYSAMEADVISEATHOTAFTERTHINGNEXTUSADDBEENBUSINESSWENTSOLIEYEARAGAINUNTILONNORTHEIRCAMEPOSSIBLEIFFORABOUTBACKALWAYSBYSATTHANAGAINSTMATTERGOTNOWCOULDNOTHINGGOINGDIDSEASUCHTHREEFOUNDBIGHASTHOSEPARTBESTLOTASKVERYRIGHTWATERHAMDUEMOREJUSTLESSLETOUTBEFOREBETWEENUSEDSHESEEWHATGOVERNMENTHOUSETWOWAYSHALLPRESENTGENERALTHETRYGOODHOMETAKENLOWTENEVENCENTFOURHADITSINTOWHILESOONBUTOILWITHBOTHWHOSESAWLAWMUSTLEFTSEVERALOURDAYCOMETELLHEREWITHTOOCANTHEMMORNINGSITUATIONHOWBIDHAVETHOUGHTCONDITIONSEATYESTHISCALLLOVEFEWWASHEREALMOSTFRONTWARYOUWILLASKEDLARGEHIMCARFIRSTHANDTHOUGHMAYYETWHICHSERVICEMINDWHOAIRMADEFIVEKEEPSAYBADWORLDMIGHTMYSELFFAROLDMUCHAMONGNECESSARYNETUSEUPONDEARWRONGWHYANYTIMEWHOLEFULLGETMANSHOULDCITYBETTERBITTHATMAKEWANTADVICE

This list of words makes excellent practice material; vary the order in which you use them so that they will not be unconsciously memorized. These words, with their variations and repetitions, are said to include more than half the words used in every-day English. Practice them until you recognize most of them by their complete sounds, instead of as a series of letters, especially ifyou want to receive with ease at heigh speeds.

Skill

When you listen to someone speaking you do not consciously think how his words are spelled. This is also true when you read. In code you must train your ears to read code just as your eyes were trained in school to read printed matter. With enough practice you acquire skill, and from skill, speed. In other words, it becomes a habit, something which can be done without conscious effort. Conscious effort is fatal to speed; we can't think rapidly enough; a speed of 25 words a minute, which is a common one in commercial operation, means 125 characters per minute or more an two per second, which leaves no time for serious thinking. Speed comes only through practice, and lots of it, however, as stated above, this does not mean long practice sessions, which are actually harmful.

Perfect Formation of Characters

When transmitting on the code practice set to your partner, concentrate on the quality of your sending, not on your speed. Your partner will appreciate it and he you do not copy you if you speeded up anyhow.

If you want to get a reputation as having an excellent "fist" on the air, just remember that seed alone won't do the trick. Proper execution of your letters and spacing will make much more of an impression. Fortunately, as you get so that you can send evenly and accurately, your sending speed will automatically increase. Remember to try to see how evenly you can send, and how fast you can receive. Concentrate on making signals properly with your key. Perfect formation of characters is paramount to everything else. Make every signal right no matter if you have to practice it hundreds or thousands of times. Never allow yourself to vary the slightest from perfect formation once you have learned it, Never mind how slowly you must send in order to be accurate. In the long run you will gain speed much more quickly if you have learned it right, and will never get much speed if you learn wrong. Everything else is secondary to perfection at this point.

If possible, get a good operator to listen to your sending for a short time, asking him to criticize even the slightest imperfections.

Timing

It is of the utmost importance to maintain uniform spacing in characters and combinations of characters. Lack of uniformity at this point probably causes beginners more trouble than any other single, factor. Every dot, every dash, and every space must be correctly timed. In other words, accurate timing is absolutely essential to intelligibility, and timing of the spaces between the dots and dashes is just as important as the lengths of the dots and dashes themselves.

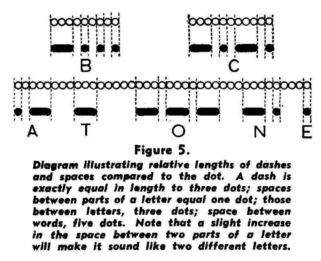

The characters are timed with the dot as a yardstick." A standard dash is three times as long as a dot. The spacing between parts of the same letter is equal to one dot; the space between letters is equal to three dots, and that between words equal to five dots! There is no such thing as long, medium, or short dashes; a dash must always equal the length of three dots, neither more nor less.

The rule for spacing between letters and words is not strictly observed when 'sending slower than about 10 words per minute for the benefit of someone learning the code and desiring receiving practice. When sending at, say, 5 w.p.m., the individual letters should be made the same as if the sending rate were about 10 w.p.m., except that the spacing between letters and words is greatly exaggerated. The reason for this is obvious. The letter L, for instance, will then sound exactly the same at 10 w.p.m. as at 5 w.p.m., and when the speed is increased above 5 w.p.m. the student will not have to become familiar with what may seem to him like a new sound, although it is in reality only a faster combination of dots and dashes. At the greater speed he will merely have to learn the identification of the same sound without taking as long to do so.

Experience has shown that it does not aid a student in identifying a letter by sending the individual components of the letter at a speed corresponding to less than 10 w.p.m. By sending the letter moderately fast a longer space can be left between letters for a given code speed, thus giving the student more time to identify the letter. There are no degrees of readability in signals. They are either right or wrong, and if they are wrong, it is usually irregular spacing or irregular dash lengths which make them so. If you find that you have a tendency towards irregularity, practice those characters which give you trouble no matter how long you must do so. Until they can be formed perfectly you are not ready for speed.

Be particularly careful of letters like B in which many beginners seem to have a tendency to leave a longer space after the dash than that which they place between succeeding dots, thus making it sound like TS. Similarly, make sure that you do not leave a longer space after the first dot in the letter C than you do between other parts of the same letter; otherwise it will sound like NN.

| KYKXQ | FVTGB | 35476 | 3V3V4 | QMWNE | PSGRT |

| LUDHW | YHNUJ | 00572 | B6B67 | RBTVY | W6DHG |

| HSUSK | MUKIL | 72649 | 4V3B7 | UXIZO | SGWYF |

| WKSOD | PLOKM | 99736 | 5HSOIP | ALSKD | AODHR |

| WOSMF | IJNUH | 26294 | W2ATF | JFHGT | W6BCX |

| KJHGF | BYGVT | 93856 | K6BZQ | PZOXI | FOSYT |

| ZQZYX | FCRDX | 22557 | FA8G6 | CUVYB | WNEYS |

| OPGJU | ESZWA | 37495 | 14PPM4 | TNRME | W6FFF |

| ASDFG | ?.,,? | 55100 | 45XVG | WQLAK | SUEHT |

| QWERT | .,.,. | 10000 | 86QHK | PGOFI | SGYOS |

| ZXCVB | ??.,, | 00009 | 86QHC | ISUAT | W6CEM |

| POIUY | ,,.?, | 26483 | LKJ55 | QBWNE | GAHEU |

| LKJHG | 12345 | 27385 | WMS7G | RNTBY | AOEHT |

| MNBVC | 67890 | 28465 | 36Y94 | OFUXY | W6KFQ |

| QAZWS | 05647 | 37495 | 117GT | YATSR | HSGEY |

| XEDCR | 28596 | 92220 | 6SQ7G | EVRNY | SYSGE |

The above list of Jumbied characters (similar to many cipher codes) will be found handy for accuracy practice; no characters can be guessed as when working from straight text. Ii is used to indicate zero in the groups containing both letters and figures.

Sending vs. Receiving

Once you have memorized the code thoroughly you should concentrate on increasing your receiving speed. True, if you have to practice with another newcomer who is learning the code with you, you will both have to do some sending. But don't attempt to practice sending just for the sake of increasing your sending speed. When transmitting on the code practice set to your partner so that he can get receiving practice, concentrate on the quality of your sending, not on your speed.

Because it is comparatively easy to learn to send rapidly, especially when no particular care is given to the quality of sending, many operators who have just received their licenses get on the air and send mediocre or worse code barely receive s remember d are only too te if you tell But the surest way to incur their scorn is to try to impress them with your "lightning speed," and then to request them to send more slowly when they come back at you at the same speed.

Stress your copying ability; never stress your sending ability. It should be obvious that if you try to send faster than you can receive, your ear will not recognize any mistakes which your hand may make.

Using the Key

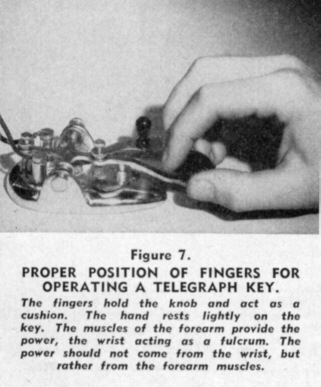

Figure 7 shows the proper position of the hand, fingers and wrist when manipulating a telegraph or radio key. The forearm should rest naturally on the desk. It is preferable that the key be placed far enough back from the edge of the table (about 18 inches) that the elbow can rest on the table. Otherwise pressure of the table edge on the arm will tend to hinder the circulation of the blood and weaken the ulnar nerve at a point where it is close to the surface, which in turn will tend to increase fatigue considerably.

The knob of the key is grasped lightly with the thumb along the edge; the index and third fingers rest on the top towards the front or far edge. The hand moves with a free up and down motion, the wrist acting as a fulcrum. The power must come entirely from the arm muscles. The third and index fingers will bend slightly during the sending but not because of deliberate effort to manipulate the finger muscles. Keep your finger muscles just tight enough to act as a "cushion" for the arm motion and let the slight movement of the fingers take care of itself. The key's spring is adjusted to the individual wrist and should be neither too stiff nor too loose. Use a moderately stiff tension at first and gradually lighten it as you ge t more proficient. The separation between the contacts must be the proper amount for the desired speed, being somewhat under 1/16 inch for slow speeds and slightly closer together (about 1/32 inch) for faster speeds. Avoid extremes in either direction.

Do not allow the muscles of arm, wrist, or fingers to become tense. Send with a full, free arm movement. Avoid like the plague any finger motion other than the slight cushioning effect mentioned above.

Remember that you are using different muscles from those which you have used previously. Give them time to become used to the new demands which you put upon them. Do not attempt to use them too long at any one time or you will overstrain them and they will not function properly for a time. If they become stiff, stop at once and exercise them for a few moments before resuming. Sit upright. Use a straight backed chair. Do not slump or slouch. Keep your feet on the floor, not way under the desk or wound around the chair legs. Stick to the regular hand key for learning code. No other key is satisfactory for this purpose. Not until you have thoroughly mastered both sending and receiving at the maximum speed in which you are interested should you tackle any form of automatic or semi-automatic key such as the Vibroplex ("bug") or the "sideswiper."

Difficulties

Should you experience difficulty in increasing your code speed after you have once memorized the characters, there is no reason to become discouraged. It is more difficult for some people to learn code than for others, but there is no justification for the contention sometimes made that "some people just can't learn the code." It is not a matter of intelligence; so don't feel ashamed if you seem to experience a little more than the usual difficulty in learning code. Your reaction time may be a little slower or your coordination not so good. If this is the case, remember you can still learn the code. You may never earn to send and receive at 40 w.p.m., but you can learn sufficient speed for all non-commercial purposes and even for most commercial purposes if you have patience, and refuse to be scouraged by the fact that others seem to pick it up more rapidly.

Never write down dots and dashes to be translated later. If the alphabet has actually been mastered beforehand, there will be no situation from failure to recognize most of characters unless the sending speed is too fast.

When the sending operator is sending just a bit too fast for you (the best speed for practice), you will occasionally miss a signal or a group of them. When you do, leave a space, do not spend time futilely trying to recall it, dismiss it, and center attention on the next letter, otherwise you'll miss more. Do not ask the sender any questions until the transmission is finished. Two or three w.p.m. over your comfortable speed is sufficient, do not let the sender go faster, or you will miss so much as to become discouraged. "Pushing" yourself moderately ve cps speed just as pushing your muscles physical strength.

To prevent guessing and get equal practice on the less common letters, depart occasionally plain language material and use a jumble of letters in which the usually less commonly used letters predominate.

As mentioned before, many students put a greater space after the dash in the letter B than between other parts of the same letter so that it sounds like TS. C, F, Q, V, X, Y and Z often give similar trouble. Make a list of words or arbitrary combinations in which these letters predominate and practice them, both sending and receiving until they no longer give you trouble. Stop everything else and stick at them. So long as they give you trouble you are not ready for anything else.

Follow the same procedure with letters which you may tend to confuse such as F and L, which are often confused by beginners. Keep at it until you always get them right without having to stop even an instant to think about it.

Watch particularly the length of your dashes. They must be equivalent to three dots, neither more nor less. Avoid dragging them out or clipping them off. Non-uniform dashes are a sure sign of a poor operator. If you do not instantly recognize the sound of any character, you have not learned it; go back and practice your alphabet further. You should never have to omit writing down every signal you hear except, when the transmission is too fast for you.

Write down what you hear, not what you think it should be. It is surprising how often the word which you guess will be wrong.

While a slow learner can ultimately get his "13 per" by following the same learning method if he has perseverance, the following system of auxiliary practice oftentimes proves of great aid in increasing one's speed when progress by the usual method seems to have reached a temporary standstill. All that is required is the practice outfit plus an extra operator. This last item should be of good quality, guaranteed to pay proper attention to spacing/

Suppose we we call the fellow at the key the teacher and the other fellow the student. Assume the usual positions but for the moment lay aside paper and pencil. Instead the student will read from a duplicate newspaper the same text that the operator is sending.

The teacher is to start sending at a rate just slower than the student's top speed, judged by his last test. This will allow the student to follow accurately each letter as it is transmitted. After a warming-up period of about one minute the sending speed is to be increased gradually but steadily and continued for a period of five minutes. An equal rest period is beneficial before the second session. Speed for the second period ought to be started at half-way between the original starting speed and the spped used at the end of the first period. Follow the same procedure for the second and third practice periods.

At the start of the third reading practice period the student should start copying immediately, using the same text as be ' fore at a speed just above his previous copying ability. It will be found that one session of the reading practice will for the time being increase the student's copying ability from 10 to 20 w.p.m. The teacher should watch the student and not increase the sending speed too much above his copying ability as this brings about a condition of confusion and is more injurious than beneficial.

Copying Behind

All good operators copy several words behind, that is, while one word is being received, they are writing down or typing, say, the fourth or fifth previous word. At first this is very difficult, but after sufficient practice it will be found actually to be easier than copying close up. It also results in more accurate copy and enables the receiving operator to capitalize and punctuate copy as he goes along. It is not recommended that the beginner attempt to do this, until he can send and receive accurately and with ease at a speed of at least 12 words a minute.

It requires a considerable amount of training to dissociate the action of the subconscious mind from the direction of the conscious mind. It may help some in obtaining this training to write down two columns of short words. Spell the first word in the first column out loud while writing down the first word in the second column. At first this will be a bit awkward, but you will rapidly gain facility with practice. Do the same with all the words, and then reverse columns.

Next try speaking aloud the words in the one column while writing those in the other column; then reverse columns. After the foregoing can be done easily, try sending with your key the words in one column While spelling those in the other. It won't be easy at first, but it is well worth keeping after if you intend to develop any real code proficiency. Do not attempt to catch up. There is a natural tendency to close up the gap, and you must train yourself to overcome this.

Next have your code companion send you a word either from a list or from straight text; do not write it down yet. Now have him send the next word; after receiving this second word, write the first word. After receiving the third word, write the second word; and so on. Never mind how slowly you must go, even if it is only two or three words per minute Stay behind.

It will probably take quite a number of practice sessions before you can do this with any facility. After it is relatively easy, then try staying two words behind, keep this up until it is easy. Then try three words, four words, and five words. The more you practice keeping received material in mind, the easier it will be to stay behind. It will be found easier at first to copy material with which one is fairly familiar, then gradually switch to less familiar material.

Handwriting vs. Typewriting

It is usually preferable to code in longhand while learning. Do not write with a cramped finger movement. Your fingers will soon get tired and will become too tense to make legible copy. Use a free arm movement. Never mind how pretty the writing is; concentrate on legibility.

It is not necessary to use a typewriter for receiving if you are learning merely for the fun of it or to become an amateur. But if you intend to go into commercial operation, by all means learn to copy on a typewriter. No matter, how rapid a handwriter you may be, you can receive much faster on a "mill." If you can already operate a typewriter by the touch system, it will not be found difficult to copy on the typewriter once you have mastered copying by hand. However, if you do not know touch typing, you have a real job ahead of you and one which is entirely beyond the scope of this book. In copying by typewriter you will feel the same tendency to catch up that you do in copying by hand, and it will be necessary to fight this tendency all over again.

Automatic Code Machines

The two practice sets which are described in this chapter are of most value when you have someone with whom to practice. Automatic code machines are not recommended to anyone who can possibly obtain a companion with whom to practice, someone who is also interested in learning the code. If you are unable to enlist a code partner and have to practice by yourself, the best way to get receiving practice is by the use of a tape machine (automatic code sending machine) with several practice tapes. Or you can use a set of phonograph code practice records. The records are of use only if you have a phonograph whose turntable speed is readily adjustable. The tape machine can be rented by the month for a reasonable fee.

Once you can copy about 10 W.P.M. you can also get receiving practice by listening to slow sending stations on your receiver. Many amateur stations send slowly particularly when working far distant stations. When receiving conditions are particularly poor many commercial stations also send slowly, sometimes repeating every word. Until you can copy around 10 w.p.m. your receiver isn't of much use, and either another operator or a machine or records is necessary for getting receiving practice after you have once memorized the code.

Code Sets Practice

If you don't feel too foolish doing it, you can secure a measure of code practice with the help of a partner by sending "did-dah" messages to each other while riding to work, eating lunch, etc. It is better, however, to use a buzzer or code practice oscillator in conjunction with a regular telegraph key.

As a good key may be considered an investment, it is wise to make a well-made key your first purchase. Regardless of what type code practice set you use, you will need a key, and later on you will need one to key your transmitter. If you get a good key to begin with, you won't have to buy another one later.

The key should be rugged and have fairly heavy contacts. Not only will the key stand up better, but such a key will contribute to the "heavy" type of sending so desirable for radio work. Morse (telegraph) operators use a "light" style of sending and can send somewhat faster when using this light touch. But, in radio work static and interference are often present, and a slightly heavier dot is desirable. If you use a husky key, you will find yourself automatically sending in this manner.

Special types of keys, especially the semiautomatic "bug" type, should be left alone by the beginner. Mastery of the standard type key should come first. The correct manner of using such a key was discussed above.

To generate a tone simulating a code signal as heard on a receiver, either a mechanical buzzer or an audio oscillator (howler) may be used. The buzzer may be mounted on a sounding board in order to increase the fullness and volume of the tone; or it may be mounted in a cardboard box stuffed with cotton in order to silence it, and the signal fed into a pair of earphones. The latter method makes it possible to practice without annoying other people as much, though the clicking of the key will no doubt still bother someone in the same room.

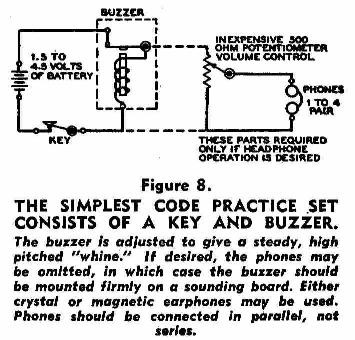

A buzzer-type code practice circuit is shown in Figure 8. The buzzer should be of good quality or it will change tone during keying; also the contacts on a cheap buzzer will soon wear out. The volume control, however (used only for headphone operation), may be of the least expensive type available, as it will not be subjected to constant adjustment as in a radio receiver. For maximum buzzer and battery life, use the least amount of voltage that will provide stable operation of the buzzer and sufficient volume. Some buzzers operate stably on 1 1/2 volts, while others require more.

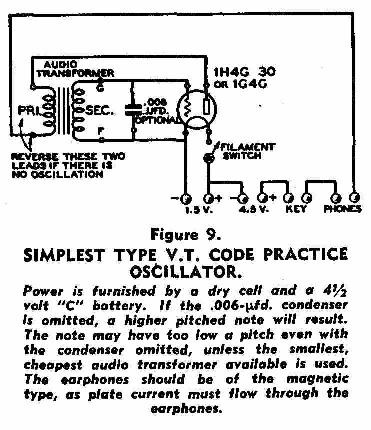

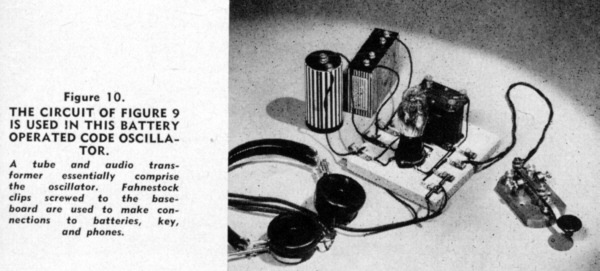

A vacuum tube audio oscillator makes the t code practice oscillator, as there is no sound except that generated in the earphones, and the note more closely resembles that of a radio signal. Such a code practice oscillator is diagrammed schematically in Figure 9. The parts are all screwed to a wood board, and connections made to the phones and batteries by means of Fahnestock clips, as illustrated in re 10. A single dry cell supplies filament power, and a 4 1/2-volt C battery supplies plate voltage. Both filament and plate current are low, and long battery life can be expected. The vacuum tube is the biggest item from the standpoint of cost, but it can later be used in a field-strength meter with the same batteries supplying power. Such a device is handy to have around a station, as it can be used for neutralizing, checking the radiation characteristics of your antenna, etc.

A lH4G, 30, or lG4G may be used with the same results. The first two are 2-volt tubes, but will work satisfactorily on a 1.5-volt filament battery because of the very small amount emission required for the low value of plate current drawn. Be sure to get a socket that will accommodate the particular tube you buy.

Oddly, it is important that the audio transformer used not be of good quality; if it is, it may have so much inductance that it will be possible to get a sufficiently high pitch. If you buy a new transformer, get the cheapest one you can buy. The older ones used in moderately priced sets of 2 years ago are fine for the purpose, and can oftentimes be picked up for a small fraction of dollar at the "junk parts" stores. The turns ratio is not important; it may be anything between 1.5/1 and 6/1.

The tone may be varied by substituting a larger (.025 ufd.) or smaller (.001 ufd.) condenser for the .006 ufd. capacitor shown in the diagram. A lower capacity condenser will raise the pitch of the note somewhat and vice versa. The highest pitch that can be obtained with a given transformer will result when the condenser is left out of the circuit altogether. Lowering the plate voltage to 3 volts will also have a noticeable effect upon the pitch of the note. If the particular transformer you use does not provide a note of a pitch that suits you, the pitch can be altered in this manner.

Using a 1H4G, a standard no. 6 dry cell for lament power, and a 4 1/2-volt C battery for the power, the oscillator may be constructed about $2.00, exclusive of key and earphones. The filament battery life will be about 700 hours, the plate battery life considerably more. This set has an advantage over an a.c. operated practice set in that it can be used there is no 110-volt power available; you can take it on a Sunday picnic if you wish. Also, there is no danger of electrical shock.

The carrier-operated keying monitor described in Chapter 24 also may be used for code practice, and is recommended where loud speaker operation is desired, such as for group practice.